Written by

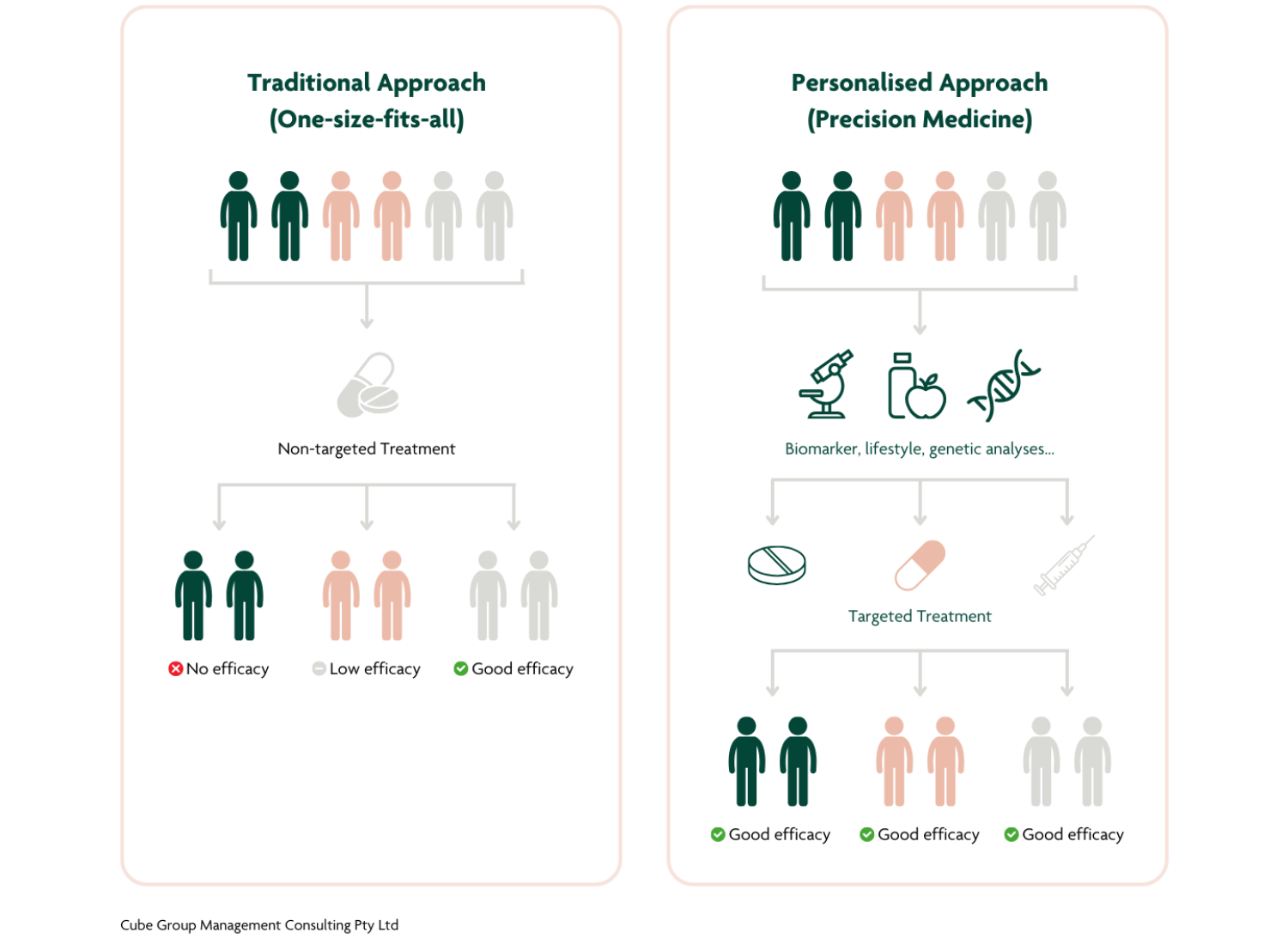

At Cube Group, we think a lot about the Australian healthcare system and the complex interactions between the myriad players, both public and private, that affect the type of care each of us receives. Exciting research into precision medicine promises great improvements in the lives and health of Australians, provided these scientific advancements can be successfully implemented into the health system. This work is important, both from a purely scientific perspective and in terms of outcomes for Australian communities. It speaks to the question of who our healthcare system is for, and how ready our community is to move away from a reactive illness-based approach towards a preventative health and wellness approach.

Read below to learn more about precision medicine, the significant benefits to wellbeing it can unlock, and the difficult conversations we need to have while integrating it into our society.

Precision Medicine

So what is precision medicine? The Australasian Institute of Digital Health has a definition:

Precision Medicine seeks and analyses a wide range of patient information, such as clinical observations, biomarkers (including genomics) and patient generated data. It triangulates this information within the context of lifestyle, behaviour, environment and medical history to inform and personalise prevention, diagnosis and treatment at an individual, patient cohort and population level. As an emerging clinical practice, precision medicine will adapt and transform over time by incorporating innovation and discovery, resulting in bespoke care.[1]

In simple terms, this means a practice of medicine that is individually tailored to you, instead of following generic guidelines based on population averages. Have you ever thought about how differently two people can respond to a glass of wine, and wondered why we are all directed to take exactly the same amount of Panadol to deal with the resultant hangover? That standard Panadol dose has been determined based on the general population. Under precision medicine, your recommended dose of Panadol could be different from mine.

Genetics Primer

The physical variations amongst human beings begin with our genes, so let’s start with a quick genetics primer. Genetics is the study of DNA.* A useful analogy is that your DNA contains all the ‘recipes’ for how to make you as a living being. Every cell in your body has a complete set of these recipes, but different cells actually ‘cook’ different meals. Your eye cells cook the recipes that allow you to see, your skin cells cook the recipes that form skin, your blood cells cook the recipes that allow them to carry oxygen or to fight infections. (As with everything in biology, there are exceptions and complications, but this simplification helps illustrate how DNA works in general). These “recipes” are billions of letters long, and the vast majority of them are identical between all humans. That is why most of us have two arms and two legs, hair covering our bodies, and an aptitude for pattern recognition. But that small amount of DNA that is different between individuals drives a lot of the tangible differences between us.** This includes visible things like hair colour and height, but also more subtle factors like how efficient your body is at processing sugar, how susceptible your arteries are to clogging, and how your organs respond to different medicine.

One of the brilliant things about precision medicine is that it allows for much more targeted and proactive approach to monitoring our health and maximising wellbeing.

* There’s a lot of words in this field that have slightly different meanings. They’re very important if you want to talk to experts, but for casual conversation you can consider “DNA”, “genes”, “genetics”, and “genomics” to all refer to the same thing: The instructions for life, found inside living cells.

**Almost everything about us is due to a combination of the environment we live in and multiple genes that interact. Height is a great example. In populations where everyone has access to complete nutrition as children, height is genetically determined. But you know that humans don’t come in just one of two distinct heights! There are lots of genes that interact to determine our exact height, some of which we know about and others that we don’t (yet). In populations where children have limited access to food, genetics plays far less of a role and height is determined mostly by nutrition.

Possibilities

It is now possible to use genetic data to predict what health concerns a person is more or less likely to face in their lifetime. It’s similar to using a family history, but it doesn’t depend on an individual having access to that knowledge. It’s also more specific – for example, genetic tests could distinguish between siblings where family history does not. This process is not a magic bullet. We don’t yet understand everything about genetics, and there are complex interactions involved that mean it’s rare that a single gene causes a single discrete effect. If your genes say you aren’t likely to get skin cancer, but you spend every summer in the sun without protection, you will probably get skin cancer anyway. But, if your genes say you are particularly susceptible to skin cancer, maybe you will choose to take special care to reapply sunscreen regularly, or wear sunscreen even in the winter.

Imagine a future where your baby’s genome is sequenced before birth. A rare genetic disease is identified that could have caused permanent developmental damage, but is easily treated because it was caught early. When they are 15 years old, you get a notification from your GP that new research has linked your child’s genes to schizophrenia. It’s not a diagnosis, but you discuss the risks with them and they decide to educate themself on early warning signs. Later in life, when they decide to have children, they and their partner’s sequences are checked for genetic combinations which could put their offspring at risk.

Challenges

The technology to create this future exists right now, and this is not even an exhaustive list of all the benefits humanity can derive from the study of genomics. But it’s important to also discuss the risks and grey zones raised by these possibilities.

The implementation challenges are significant. What if someone doesn’t want their baby’s genome sequenced? What if the teenager suffers severe anxiety over the schizophrenia that never actually materialises? What if sequencing reveals unwanted family history? What if the health system becomes overrun with people seeking treatment for health problems that they don’t even have? What if someone wants to preferentially select an embryo based on eye colour? Or how good a soldier they might turn out to be? And what if only some people in society have the means to make these choices?

So you can see, there can be downsides to knowing your genetic risk factors, and the data science has a way to go before we can make predictions with complete accuracy. But the key takeaway is that the more knowledge we have about our risk factors, the better able we are to make informed decisions about how to live our lives. And the accuracy of the predictions will only improve with more data and advances in AI.

But there are other factors that also act as barriers to the uptake of genetic testing. Barriers that are not inherent to the science and are instead dependent on economic systems.

Example: Life Insurance

This tension is playing out right now in the field of life insurance. Here is where I want to introduce an issue that the Commonwealth government is currently seeking public input on – the use of genetic testing results in life insurance underwriting.

Private life insurance companies offer different rates to people based on risk factors – including genetic risk factors. Life insurers are legally entitled to existing genetic information when you apply for a plan. But this doesn’t just affect people at the point of applying for life insurance. Studies show that the risk of affecting hypothetical life insurance applications far into the future does in fact stop people from taking genetic tests that could help them make better informed decisions about their health and wellbeing.[2]

From 2019, life insurers entered a voluntary agreement (which has since been incorporated into the Life Insurance Code of Practice) not to use genetic test results to plans under a certain financial limit. This agreement was not legally binding and doesn’t apply to plans over $500,000 (which is actually lower than average). In 2023, Monash University researchers (led by Dr Jane Tiller) released their final report of the Australian Genetics and Life Insurance Moratorium: Monitoring the Effectiveness and Response (A-GLIMMER) Project, with two major recommendations:

1. The Australian Government amend the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Cth) to prohibit insurers from using genetic or genomic test results to discriminate between applicants for risk-rated insurance, and consider amendments to the regulation of financial services to ensure insurers are subject to a positive duty to not discriminate.

2. The Australian Government allocate responsibility and appropriate resources to the Australian Human Rights Commission (‘AHRC’) to enforce, promote, educate and support individuals and all relevant stakeholders to understand and meet the new legal obligations under the Act. The AHRC should consult with a range of genetics and genomics experts and stakeholders to achieve this goal.

This brings us back to the consultation currently underway by the Treasury: Use of genetic testing results in life insurance underwriting. Treasury is asking the public to have their say on this issue up until 31 January 2024. The consultation paper proposes a number of questions, but the key is selecting from three proposed options:

Option 1: No Government intervention

Option 2: Legislating a ban

Option 3: Legislating a financial limit

No government intervention means exactly that – the government would take no action and allow life insurers to continue to self-regulate. A complete ban would mean Australians can undergo genetic testing without concerns about the effect on any future life insurance. Similar bans are already in place in Canada, Singapore, and the UK, with minimal impact to life insurance industries.[3] Legislating a financial limit would make the current voluntary agreement (or something like it) into law. Patient advocacy groups warn that this would leave insurers with loopholes, and would not solve the problem of discouraging genetic testing. It also leaves geneticists the unenviable job of having to provide legal and financial advice to their patients, something they are not trained to do. We encourage all Australians to embrace their curiosity and learn more about this important topic. You can add your voice to this debate by visiting this website. Read more from A-GLIMMER here, click here for the full report, or click here to read the Treasury consultation paper.

Final Words

Embracing the possibilities of precision medicine means a shift towards a healthcare system that is proactive, ultimately more efficient to run, and leads to a better, healthier society with people empowered to make decisions about their health. This is the natural next step for Australia, but there will be difficulties in implementation. I am looking forward to writing more about precision medicine, the promise it holds, and the tough challenges that we need to solve to realise these benefits.

About the Author

Carla Carroll is an associate at Cube Group. A keen program manager and strategic planner specialising in the biomedical and health fields, Carla’s work focuses on the use of technology in achieving an equitable society. Carla is committed to public value and its role in improving society for all Australians.